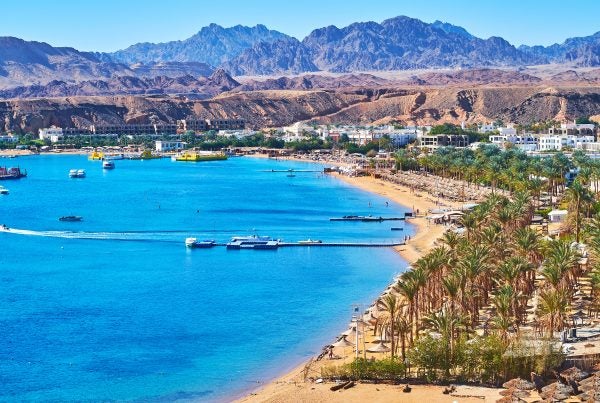

SHARM EL-SHEIKH–Members of communities in the U.S. Gulf Coast stood in solidarity at Cop27 with residents of developing nations who experience the harmful effects of methane emissions from fossil fuels and industry.

“We are suffering from the same polluters,” said Dr. Beverly Wright, executive director of the Deep South Center for Environmental Justice.

The oil and gas industry is the largest source of industrial methane pollution and a huge source of volatile organic compounds that cause health problems in vulnerable communities around the world. Proposed solutions for communities living near industrial sites tend to fall short, creating a cycle of harm that can be almost impossible to escape.

Whether it’s Johannesburg or Baton Rouge, it’s often communities of color who suffer the most as a result of methane and other co-pollutants emitted by the oil and gas sector and other industries, such as petrochemicals. “People of color and limited financial means live far different lives than their whiter, wealthier counterparts,” Wright said.

As wealthier people in the United States have moved away from industrial areas, poor people have not had the same opportunity. Instead, they are often forced to live their lives near industrial zones whose methane emissions trigger a number of health issues.

Cancer Alley, for example, is a stretch between Baton Rouge and New Orleans in the southern U.S. that contains over 150 petrochemical plants and refineries. The area accounts for 25% of U.S. petrochemical production, and its residents have a cancer rate 50% higher than the national average.

Across the U.S., more than 14 million Americans live in counties where emissions levels are above limits set by the Environmental Protection Agency, said Lindsey Baxter Griffith, federal policy director for the Clean Air Task Force.

Thousands of miles away, the problems are similar. In Johannesburg, pollution has reduced life expectancy by an estimated three years. In Tanzania, the average life expectancy is just under 66, about seven years lower than the global average, according to World Bank data. Tanga is home to the largest milk processing plant in Tanzania, an operation that is a significant source of methane emissions.

But Wright said the solutions are unlikely to come from industry. “The same people who cause the problem come up with solutions that endanger the same group of people,” Wright said, calling this a “come to Jesus moment for many of us.”

EPA Administrator Michael Regan envisions a different path forward for the communities most at risk, one in which technology, data and impacted communities play key roles.

“Solutions come from communities. It’s our job to match the resources to the solutions in the community,” he said.